This issue of Esopus—our first annual edition—explores the intersections between the world of medicine and the world of art. Its contributors include artists, physicians, writers, psychiatrists, filmmakers, poets, hospitalists, archivists, medical illustrators, dentists, musicians, interior designers, phlebotomists, photographers, graphic novelists, teachers, and nurses.

Some fall into more than one category. The late poet and doctor William Carlos Williams is represented here by never-before-published prescription pads containing his notes for poems, plays, and essays jotted down between patient visits. Paul Austin, an emergency-room physician and the author of the 2008 memoir Something for the Pain, introduces a selection of 100 frames from Frederick Wiseman’s classic 1970 documentary Hospital. Comic artists MK Czerwiec and Ian Williams, who make their living as a nurse and doctor, respectively, offer excerpts from their forthcoming graphic novels detailing the challenges and rewards of their profession. For the artist’s project Singles, psychiatrist and artist Martin Wilner has crafted meticulous drawings using the same musical model he employs when listening to the encoded “melodies, motifs, and rhythms” of his analysands.

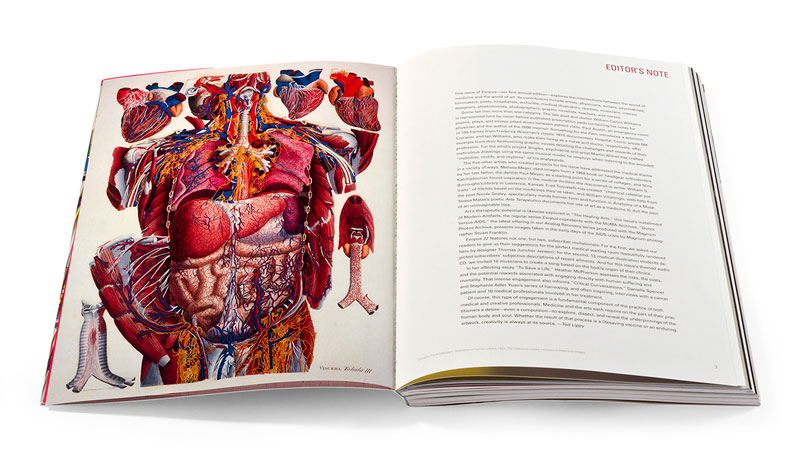

The five other artists who created projects for the issue have addressed the medical theme in a variety of ways. Melissa Meyer used images from a 1968 book on headgear orthodontics by her late father, the dentist Paul Meyer, as a starting point for a series of collages, and Nina Katchadourian found inspiration in the medical thrillers she discovered in writer William S. Burroughs’s library in Lawrence, Kansas. Fred Tomaselli has created “chemical celestial portraits” of friends based on the medicines they’ve taken, and William Villalongo, with help from the poet Nicole Sealey, spectacularly melds human form and function in Anatomy of a Muse. Teresa Matas’s poetic Arte Terapéutico documents her use of art as a medicine to dull the pain of an unimaginable loss.

Art’s therapeutic potential is likewise explored in “The Healing Arts,” this issue’s installment of Modern Artifacts, the regular series Esopus copresents with the MoMA Archives. “Durex Versus AIDS,” the latest offering in our Analog Recovery series produced with the Magnum Photos Archive, presents images taken in the early days of the AIDS crisis by Magnum photographer Stuart Franklin.

Esopus 22 features not one, but two, subscriber invitationals: For the first, we asked our readers to give us their suggestions for the perfect medical waiting room (beautifully rendered here by designer Thomas Juncher Jensen); for the second, 13 medical-illustration students depicted subscribers’ subjective descriptions of recent ailments. And for this issue’s themed audio CD, we invited 10 musicians to create a song based on the bodily organ of their choice.

In her affecting essay “To Save a Life,” Heather McPherson assesses the risks, the costs, and the potential rewards associated with engaging directly with human suffering and mortality. That intense engagement also informs “Critical Conversations,” Danielle Spencer and Stephanie Adler Yuan’s series of harrowing, and often inspiring, interviews with a cancer patient and 10 medical professionals involved in her treatment.

Of course, this type of engagement is a fundamental component of the practice of both medical and creative professionals. Medicine and the arts each require on the part of their practitioners a desire—even a compulsion—to explore, dissect, and reveal the underpinnings of the human body and soul. Whether the result of that process is a lifesaving vaccine or an enduring artwork, creativity is always at its source.